A famous Serbian/Montenegrin hiker and primarily a great man, Krsto Zizic or Ziza as we who thanks to him saw and got to know so many beautiful mountain landscapes of the Balkans used to call him, used to take a group to northern Greece each year, around mid September. For who knows which reason, I managed for years NOT to go on this tour, but luckily in 2006 I organized myself sufficiently well as to join a large group of hikers who went on this trip that lasted for some 10 days. The tour included climbing to the highest peak of mount Olympus, September vacationing on the beaches of Greece and a one-day trip to Meteora monasteries, but the most important reason for the tour was the regular marking of the anniversary of the breach of the Macedonian or the Thessaloniki front (WWI), including a visit to Kaymakchalan, military cemetery Zeitenlik in Thessaloniki and attending a ceremony at the WWI Memorial in Polycastro.

The first destination on our trip was Kaymakchalan. This is the highest peak of the mountain range Voras (this is what the Greeks call it, the Macedonians call it Nidze) with the altitude of 2521 m a.s.l. and it is located at the very border between Greece and Macedonia (the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia or the FYROM). On the slopes of the mountain there are also terrains used for skiing during winter, which may be concluded by the existence of a ski lift. Thus, after a night’s drive directly from Belgrade, early in the morning the coach brought us to the place where the ski lift begins and where the asphalt road ends. After a short break, the hikers started their ascent to Kaymakchalan on foot.

Slopes of the Voras mountains

Slopes of the Voras mountains

The peak itself is within the border zone and it is not envisaged for people to wander around just like that, so to start with before the trip Ziza had to send a list of participants to the Greek army which secures this section and a couple of Greek military border guards accompanied the group heading for the peak. They actually followed the group in a small vehicle that had a cabin in the back. Since in the period before going to Kaymakchalan I wasn’t very active as a hiker and had some health problems, I was actually very unfit. I did start on foot with the group along a very steep slope, but I soon gave up and when the vehicle passed by me I asked the Greek soldiers if, in addition to a couple of hikers who were already in the cabin, they could take me as well. This eventually turned out to be a great thing because I was among the first visitors which allowed me to see and take photos of some things without too many people in the picture. I was also first to get down into the charnel house, which was important as there was no crowd there.

Kaymakchalan is the place where in 1916 there was a battle between the Serbian and the Bulgarian armies during WWI. This entire area was a part of the Thessaloniki or the Macedonian front and in this sector the Bulgarians held the peak, while the Serbs had the task to take it. Preparations for the battle started on 12 September and the attack ensued on 16 September 1916. There was a lot of tug-of-war, but by the end of the month and with a high number of fatalities, the Serbs managed to win the battle.

90 years later, exactly on 16 September, the vehicle brought a couple of us just under the peak itself and that last segment had to be covered on foot and I was again in a situation in which I was getting out of breath on account of the steep slope I was walking along. There, across the entire clearing covered only by grass, it is still possible to see remains of trenches, as well as rusted remains of barbed wire from the First World War and that only reminded me of the events that reached their peak here in September 1916. As I’ve said, the task of the Serbian army was to conquer the peak held by the Bulgarian army. I felt almost ashamed because it was so difficult for me to go up the hill as a leisurely tourist, while my ancestors had to cover that same steep slope under a heavy fire of the Bulgarian artillery. The final conquest of the peak took place on 30 September and it was a very emotional moment for the Serbian army for at the time this was a borderline between Greece and the Kingdom of Serbia, so the taking over of the peak on whose other side was practically the territory of Serbia symbolized the final beginning of “homecoming,” since in 1915 when faced with the attacks of the German and Austro-Hungarian forces the entire army was compelled to leave the country in order not to capitulate.

90 years old barbed wire

90 years old barbed wire

Today, at the very top, there is a small memorial chapel dedicated to Saint Elijah. It is in a rather shabby condition, but it is not unusual for many years have passed, many things have happened and it is not in a suitable place for regular visits and maintenance.

Memorial chapel of St. Elijah on Kaymakchalan

Memorial chapel of St. Elijah on Kaymakchalan

The fence around the plateau on which the chapel is built is made of the leftover artillery ammunition, as well as of intertwined barbed wire.

The fence around the chapel of St. Elijah on Kaymakchalan

The fence around the chapel of St. Elijah on Kaymakchalan

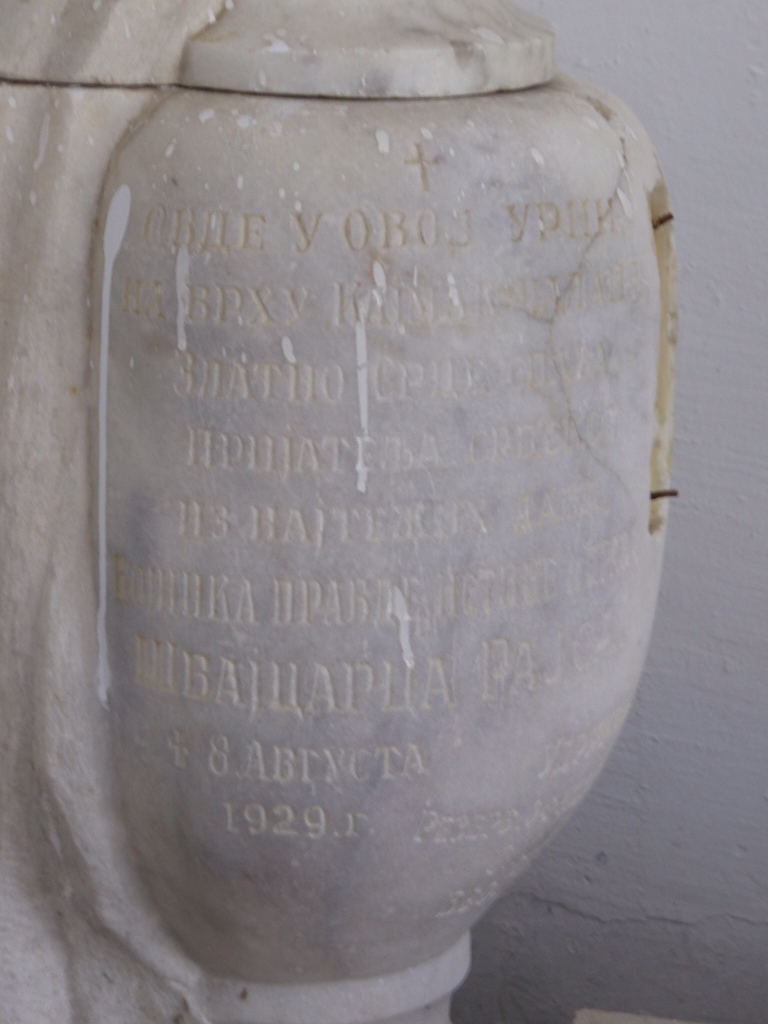

When one enters the chapel itself, there is an impression of major dilapidation, the floor is damaged and there is some wooden door placed over it (or at least this was what it looked like in 2006). In the sanctuary space there was a table with different gifts somebody had left there, there were some old wreaths and the entire wall opposite the entrance was covered in icons. Still one of the most valuable things that could be seen there is a white marble urn that is placed on the right-hand side from the entrance.

The urn in the chapel of St. Elijah

The urn in the chapel of St. Elijah

This urn is where the heart of Archibald Reiss, a great friend of the Serbian nation, used to be. Archibald Reiss (1875-1929) was a German-Swiss criminologist and forensic scientist, and he also used to be a professor at the University of Lausanne. In 1914 he came to Serbia at the invitation of the Serbian government in order to investigate the crimes of the Austro-Hungarian army over civilian population. He came, fell in love with Serbia and the Serbs, and stayed with them until his death in Belgrade in 1929. At his expressed desire, his heart was placed in an urn and brought here to Kaymakchalan, while his body was buried at the Topcider cemetery (Topcidersko groblje) in Belgrade. Over time, the heart from the urn disappeared and although there are several different stories and suppositions as to what really happened to it, the most probable version is that it disappeared during the Second World War when this area was again taken by the Bulgarian army.

The urn, however, did survive and there is an engraving on it:

“Here in this urn,

on top of Kaymakchalan

a heart of gold sleeps,

a friend of Serbs

from the direst days,

a hero of fairness, truth and justice,

Reiss the Swiss, may he rest in glory.”

There is also an engraving of the date of his death – 8 August 1929.

The urn in which the heart of Archibald Reiss used to be

The urn in which the heart of Archibald Reiss used to be

When you leave the chapel, you can see a stone cuboid down the slope surrounded by small pillars. This is where the charnel house of the Serbian soldiers who were killed in Kaymakchalan is. That is, a part of the remains has been transferred to Thessaloniki, to the military cemetery in Zeytinlik, while the rest has been collected here. At the stone plateau surrounding the cuboid, there is a lid-covered square entrance into the charnel house and when you remove that lid it is possible to go down metal ladder.

The charnel house at Kaymakchalan

The charnel house at Kaymakchalan

The charnel house at Kaymakchalan, with a view at the memorial chapel of St. Elijah

The charnel house at Kaymakchalan, with a view at the memorial chapel of St. Elijah

As I’ve mentioned, I was the first to reach the charnel house with another hiker, so the two of us removed the lid and one after the other went down.

The charnel house at Kaymakchalan

The charnel house at Kaymakchalan

The charnel house at Kaymakchalan

The charnel house at Kaymakchalan

The experience is specific not only because of the place itself and its nature, but also because of the awareness that remains of the heroic ancestors of my nation are placed there. The battle of Kaymakchalan is considered in our collective memory as one of the most glorious victories won by the Serbian army. Still, the Serbian soldiers had to wait for the final return to their homeland and their homes for two more years, because the Macedonian front was only breached in September 1918.

We, who came here as tourists, gathered around the coach a little while later and then we were taken to a place on the coast where we stayed for a week. Serious hikers used this time to climb mount Olympus, while I went with my friends for nice walks around some nearby flat parts of Greece. Still, this was also an opportunity to go for a one-day visit to the famous Meteora (monasteries).

The Meteora is name for a group of monasteries in the north of Greece, in the region of Thessaly. Near the place Kalambaka, there is a very unusual geological formation where huge rocks, like columns, rise from the surrounding vegetation and provide for a link between the flatlands and the mountain massif. In the 11th century, first hermits started to live in caves that may be found within this formation and then over time proper monasteries were built on their tops. For a long period of time, the monasteries were accessible only by rope ladders or baskets that could be pulled up into the monasteries when not used which would ensure their complete inaccessibility and privacy. Today, all of the monasteries may be reached by an asphalt road, or rather, it is possible to get near to some of them and then it is necessary to follow the paths and steps carved into the rocks until reaching the entrance.

St Stephen’s Monastery, the Meteora

St Stephen’s Monastery, the Meteora

In the 15th and the 16th centuries, there used to be 24 active monasteries here, but this number fell to only four in the second half of the 20th century. Nowadays, there are six active monasteries – St Stephen’s Monastery (Agios Stefanos), Holy Trinity Monastery (Agia Triada), Monastery of Roussanou/St. Barbara, Monastery of Varlaam, Monastery of Great Meteoron (Megalo Meteoro) and Monastery of St. Nicholas (Agios Nicholaos). Some are male and some are female. The monasteries are very traditional, which means that when one wants to visit them it is necessary to be decently dressed and in line with the tradition; in other words, no bare arms and legs, but rather long trousers or longer skirts and longer sleeves. For those who forget to bring with them appropriate clothing, the monasteries provide pieces of clothes that may be borrowed for the occasion. It is also important to bear in mind that not all the monasteries are open every day and during the entire day. When one plans a visit, it is advisable to check the opening hours of the monasteries in order to make a selection, but if there is time, it would also be nice to stay at one of the numerous hotels in Kalambaka and visit the monasteries over a couple of days.

Holy Trinity monastery, the Meteora

Holy Trinity monastery, the Meteora

Monastery of Roussanou, the Meteora

Monastery of Roussanou, the Meteora