When I travelled throughout Latin America before, both in the countries north and south of Colombia, I used to regularly take advantage of locally organised tours. I always saw this as a major advantage of these destinations. Often, even before the trip, I could find out from guidebooks what was locally organised and offered. As soon as I arrived in a place, I would visit local agencies and sign up for tours almost immediately upon entering the first agency I found, as prices were usually practically the same. In addition to paying for the tour, you would also give the name of your hotel and then they would pick you up there at the appointed time, as part of a small group of independent travellers who had also signed up for that tour. And it worked perfectly.

I came to Colombia with the idea that I would similarly take locally organised tours from larger cities because it is much easier this way.

However, even before leaving Belgrade, I saw on the internet what was being offered and was surprised by the disproportionately high prices of these tours. I thought maybe it was because reservations were requested online in advance, so I left everything for Bogota itself.

During my first day in the capital city of Colombia, I embarked on a rather ambitious walk through the old part of the city, La Candelaria. Among other things, I intended to find a local tourist agency. The receptionists at my hotel recommended one agency in the heart of the city and, as it turned out, there weren't any others in that part of Bogota. So, during my stroll, I visited that agency with the intention of booking two tours for the coming days.

It turned out that the information I found online was accurate and reflected the prices I encountered locally. When it comes to my travels, I never question local prices, especially when there are two pricing structures (for foreigners and locals), because I believe that ultimately the decision is mine – either I can afford something or I can't, and if I inquire about something, I definitely have the desire for it. In addition, over time, I've become more willing to pay more for services if they will “get the job done” for me.

However, these prices for day trips from Bogota (and, by the way, there was no difference between prices for foreigners and locals) were indeed, in my opinion, far too high. On the other hand, the woman working at the agency also informed me that there were no tours scheduled for the next few days because no one had signed up. That didn't surprise me at all.

All in all, I realised that I would have to organise my own excursions and perhaps adjust my travel plans. Well, when you have to do it, it’s not difficult.

However, after that dry cough that started waking me up just before dawn, I woke up with an apparent sense that I was catching a cold. It was quite clear to me that it was all due to the stresses of the past few days, but knowing this did not help me at all. I always bring my little “pharmacy” with me on trips, but since my backpack hadn't arrived, it also meant that all the medications I had prepared were far away (specifically in New York). I also realised that I would need to visit a local pharmacy soon in order to help my body deal with the issues.

So, for the second day of my stay in Colombia, I decided to go on a trip to the town of Zipaquirá, which is located about 40 km north of Bogotá. Here is a map showing the places I visited during my stay in Colombia.

Although there is a tourist train said to be interesting for the journey from Bogotá to Zipaquirá, it runs quite slowly (3 hours one way), stays too short a time in Zipaquirá to see everything and then takes even longer to return to Bogotá. In other words, this option didn't work for me, at least not practically.

Another way to get to Zipaquirá is by taking an intercity coach from the Portal del Norte station, while to get there, it is best to take a city bus that belongs to the TransMilenio system.

I've mentioned before that Bogotá has around 8 million inhabitants. All these people need to move around the large city and in the absence of rapid transit systems like an underground train system, they've designed a bus system that uses specially designated lanes where other traffic isn't permitted, allowing these buses to move much faster from one end of the city to the other. This system is called TransMilenio and it uses specific bus stops. To enter a station, visitors like me need to have a plastic transport card for the city, which can be topped up as needed.

When I set out from the hotel towards the nearest TransMilenio station in the morning, I wasn't entirely clear on how everything worked. Namely, when I searched online for information, everything was described in too many general details without giving practical and concrete advice. I imagined I could just go to the station and buy a single ride ticket. I was wrong.

Upon arriving at the station, I had to pass through the turnstiles that allow passengers through one by one. I didn't see a ticket counter where I could buy a single ticket, so I asked the security guard how to proceed. He asked me where I was going and when I told him, he showed me that I should jump over the turnstile and just go through. I was momentarily confused, but he was the guard, so I followed his instructions.

Soon, the bus arrived, which turned out to go directly to the Portal del Norte station and I found a free seat for myself. I rode for almost an hour because despite the dedicated lane for these buses, the distance was about 20 km and there were traffic lights at intersections that everyone had to obey, even the "fast" buses.

On a city bus in Bogotá

On a city bus in Bogotá

By the way, I later realised that you can’t buy single tickets for public transportation in Bogotá. You must purchase a plastic card and then add money to it as needed. Every time you enter a TransMilenio bus station, you scan the card and the fare is deducted from its balance. The same system applies when boarding regular buses – you also have to scan the card, but inside the bus.

When I arrived at the Portal del Norte station, I exited the platform and right there were intercity coaches waiting, including one heading to Zipaquirá. I left Bogotá within 5 minutes.

I enjoyed sitting idly on the coach because I wasn't feeling very well, but once I arrived at the coach terminal in Zipaquirá, I had to start walking. The city centre wasn't far from there.

Along the way, I passed by a spot on the sidewalk where a woman was selling freshly fried empanadas and I felt the urge to try one. It was excellent.

Empanada in Zipaquirá

Empanada in Zipaquirá

This empanada reminded me of something.

Back in the day, I worked at an organisation where my boss was a Spanish man. Since his wife had her career at a university in Spain, it meant that José Luis spent most of the year alone in Belgrade. For that reason, he brought with him a cookbook with Latin American specialties “for singles,” which I happened to copy on one occasion, even though objectively, José Luis ate “zander with Swiss chard” in at least 90% of cases. How do I know this? Simply put – the woman who maintained and cooked at his flat called every day to ask what he wanted to eat for lunch and the answer was almost always “zander with Swiss chard.” However, after returning from Colombia, I decided that at least I, after a couple of decades, would use that cookbook, so here is a recipe for Colombian empanadas.

EMPANADAS COLOMBIAN STYLE

Pastry:

- 240 g all-purpose flour

- 1/2 tsp of salt

- 1/4 tsp of ground turmeric

- 115 g cold butter

- 1/2 tsp of freshly squeezed lemon juice

- 120 ml water

Mix the dry ingredients together. Then, using your fingers, incorporate the butter that has been diced into small pieces. Once the mixture resembles coarse sand, add the combination of lemon juice and water, and bring everything together into soft dough. Be careful not to over-knead; just combine until it forms cohesive dough.

Place the dough in a bowl, cover it and refrigerate for about half an hour. Then roll out the dough thinly with a rolling pin and cut out circles using a cutter. Place a small amount of filling in the centre of each circle, fold the dough over and press the edges firmly together, sealing them by pressing with a fork.

Filling:

- 220 g ground pork

- 1 onion, finely chopped

- salt, pepper and cumin (to taste)

- 2 tbsp of capers

- 1 hard boiled egg, chopped

- 110 g cooked red beans

Sauté the onion until translucent, then add the meat and spices, and continue to shallow fry until the pork is cooked. Once cooled, combine this mixture with the remaining ingredients and use it to fill the empanada dough.

Finally, fry them in deep oil. These empanadas can also be baked in the oven. First, brush them with beaten egg, then bake in a preheated oven at 180 degrees Celsius for about 20 minutes.

Colombian empanadas à la moi

Colombian empanadas à la moi

And as for Zipaquirá, although the town itself isn't the main reason visitors come here, I must admit I was delighted when I arrived at one of its two main squares, which is the Main Park or Parque Principal. Actually, some houses near this spacious square or even around it were exceptionally charming.

Zipaquirá, a detail

Zipaquirá, a detail

Zipaquirá, a detail

Zipaquirá, a detail

From the corner where I arrived at the square, I also took a picture of it, but I saved the stroll through it for a little later.

Zipaquirá, Parque Principal

Zipaquirá, Parque Principal

For now, I walked between those two lovely houses towards another spacious square, the Independence Square or Plaza de la Independencia.

Zipaquirá, a detail

Zipaquirá, a detail

Zipaquirá, Independence Square

Zipaquirá, Independence Square

This second square is slightly different in design compared to the main square, but it's certainly beautiful. I looked around for a place to have coffee and also scoped out where I might have lunch later.

Zipaquirá, Independence Square, a detail

Zipaquirá, Independence Square, a detail

What I also saw here were a couple of American black vultures (Coragyps atratus). It was quite evident that these birds are present in Colombia in significant numbers.

American black vultures

American black vultures

After a pleasant coffee break, I returned to the main square and took a closer look around. Neither the square nor the town of Zipaquirá are known for significant architectural landmarks, but I thoroughly enjoyed walking around the centre. For example, there is a beautiful City Hall building and a church, which is actually the official cathedral (it will soon be clear why I’m emphasising this), constructed over 100 years ago. Unfortunately, the church was closed.

Zipaquirá, Town Hall and a colonial building

Zipaquirá, Town Hall and a colonial building

Zipaquirá, the Cathedral

Zipaquirá, the Cathedral

There are other beautiful buildings around the square, but since I wasn't feeling quite well, I just took some superficial photos of them and didn't explore further.

Zipaquirá, Parque Principal, a detail

Zipaquirá, Parque Principal, a detail

Zipaquirá, Parque Principal, a detail

Zipaquirá, Parque Principal, a detail

The same applied to the square itself – I just took photos of it with my mobile phone and camera, but I wasn't in the mood for walking around or doing any sightseeing.

Zipaquirá, Parque Principal

Zipaquirá, Parque Principal

Zipaquirá, Parque Principal

Zipaquirá, Parque Principal

I found a pharmacy at the square and bought a general-purpose medication for colds and similar problems. My cough wasn't calming down and I felt quite heavy. The good thing was at least I didn't have a fever.

Now, I was already mentally prepared, if not physically, to go and see the main reason why most visitors come to Zipaquirá. It is a cathedral, but not just any cathedral. It is a cathedral made of salt. Let me explain.

Once upon a time (about 250 million years ago), the terrain that now surrounds Zipaquirá was at the bottom of the sea. When the Andes began to rise, the seabed along with the salty water that formed the newly created lake started to rise, too. Over time, the lake dried up and the salt deposits ascended to over 2700 meters above sea level. A few other examples of such geological events can be seen in my travel stories from Bolivia:

https://www.svudapodji.com/en/santa-cruz-sucre-and-potosi-the-three-tiered-cities-part-2-peru-and-bolivia-summer-2005/ and https://www.svudapodji.com/en/salar-de-uyuni-peru-and-bolivia-summer-of-2005-part-2/.

When the Spanish conquistadors arrived in these lands, the Muisca people were already mining salt extensively near Zipaquirá using open-pit methods on nearby hills. This method continued even after the Spanish settled in the area. It wasn't until the early 19th century that underground mines were developed to extract larger quantities of salt. Over time, these methods evolved and nowadays modern technologies are used for the extraction. Interestingly, approximately half of the salt used in Colombia today still comes from mines in this region.

In 1932, miners on a hill west of downtown Zipaquirá created a small sanctuary where they could pray before starting their work. By 1950, this sanctuary had evolved into a larger church, which was inaugurated in 1954 and operated until 1992. Due to concerns about potential collapse, stemming from ongoing mining activities, it was closed. Immediately, plans began for a new church, which was inaugurated in 1995.

Therefore, this is the only underground cathedral in the world and this is the main reason why a large number of visitors, both foreign and domestic, come to Zipaquirá.

The entrance to the former mine is on that hill above Zipaquirá, but it was clear to me that given my physical condition, I wouldn't be able to climb up to it. So, I intended to take a taxi in order to go quickly up the hill to the entrance and the place where I could buy a ticket. By the way, due to various stories circulating in the wider world about security in Colombia, I asked a kind gentleman if it was safe for me to hail a taxi on the street. He assured me it was safe indeed and even mentioned a reasonable fare. All my interactions with Colombians so far had unequivocally shown them to be extremely polite, kind and helpful people who were eager to assist.

So, I took a taxi, went up the hill and from there, I first took in the surroundings.

Zipaquirá, a detail

Zipaquirá, a detail

Then I waited in line for a bit and bought a ticket. Along with it, I received an audio guide. This suited me much better than going on a tour with a group and a guide, which is actually the common practice when visiting the Salt Cathedral.

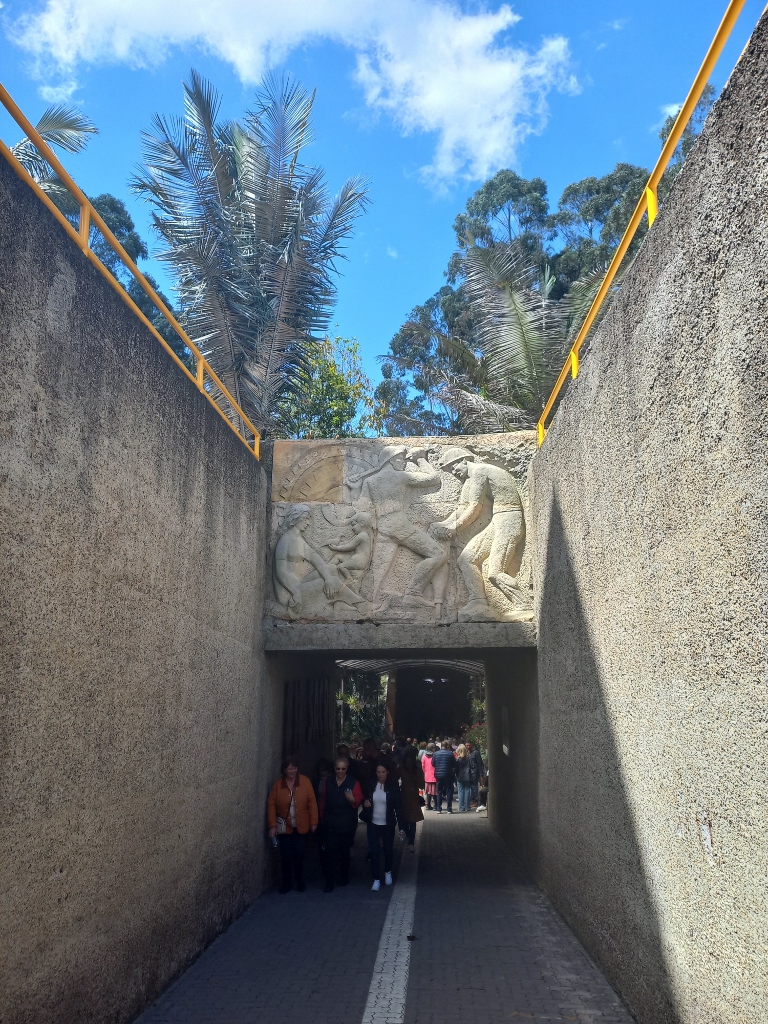

Entrance into the former mine with the Salt Cathedral

Entrance into the former mine with the Salt Cathedral

Namely, you enter the former mine in groups – the staff allow a certain number of visitors at a time, while others have to wait their turn. However, once inside, no one will insist that you walk around as part of that group.

That’s how I entered and then I started using my audio guide.

First, you pass through a long corridor that alternately lights up in different ways, some of which are quite psychedelic. At least that's how it seemed to me.

Access hallway of the mine with the Salt Cathedral

Access hallway of the mine with the Salt Cathedral

Access hallway of the mine with the Salt Cathedral

Access hallway of the mine with the Salt Cathedral